A colleague of mine, Eric Charnesky, asked me if C#6 language features would work in .NET Framework versions other than 4.6. I was pretty confident that the features were almost all1 just syntactical seasoning, I thought I would find out.

The TL;DR is yes, C#6 features will work when compiled against .NET 2.0 and above, with a few caveats.

- Async/await requires additional classes to be defined since the Task Parallel Library, `IAwaitable` and other types were not part of .NET 2.0.

- The magic parts of string interpolation need some types to be defined (thanks to Thomas Levesque for catching this oversight).

- Extension methods need the declaration of `System.Runtime.CompilerServices.ExtensionAttribute` so that the compiler can mark static methods as extension methods.

Rather than just try .NET 4.5, I decided to go all the way back to .NET 2.0 and see if I could write and execute a console application that used all the following C#6 features:

- Expression-bodied members

- `using static`

- Exception filters

- String interpolation

- Auto-property initializers

- `Add` extension methods in collection initializers

- `nameof` operator

- Index initializers

- Null-conditional operators2

The code I used is not really important, though I have included it at the end of this post if you want to see what I did. The only mild stumbling block was the lack of obvious extension method support in .NET 2.0. However, extension methods are a language-only feature; all that is needed to make it work is an attribute that the compiler can use to mark methods as extension methods. Since .NET 2.0 doesn't have this attribute, I added it myself.

Exclusions

You might have noticed that I did not verify a couple of things. First, I left out the use of `await` in `try`/`catch` blocks. This is because .NET 2.0 does not include the BCL classes that the compiler expects when generating the state machines that drive async code. You might be able to find a third-party implementation that would add support, but my brief3 search was fruitless. That said, this feature will definitely work in .NET 4.5 as it is an update to how the compiler builds the code.

Second, I did not intentionally test the improved overload resolution. The improvements mostly seem to relate to resolution involving overloads that take method groups and nullable types. Unfortunately, in .NET 2.0 there was were no `Func` delegate types nor nullable value types (UPDATE: Nullable types totally existed in .NET 2.0 and C#2; thanks to Thomas Levesque for pointing out my strange oversight here – I blame the water), making it difficult to craft an example that would demonstrate this improvement. However, overload resolution affects how the compiler selects which method to use for a particular call site. Once the compiler has made the selection, it is fixed within the compiled output and as such, the version of the .NET framework has no bearing on whether the resolution is correct4.

Did it work?

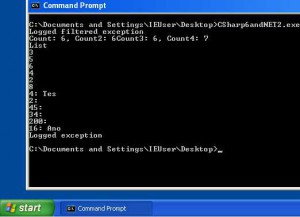

With the test code written, I compiled and ran it. A console window flickered and Visual Studio returned. The code had run but I had forgotten to put anything in there that would give me chance to read the output. So, I dropped a breakpoint in at the end, and then ran it under the debugger. As I had suspected it might, everything worked.

Then I realised I was still executing it on a machine that had .NET 4.6 and therefore the .NET 4 runtime; would it still work under the .NET 2 runtime? So, I cracked open5 a Windows XP virtual machine from modern.ie and ran it again. It didn't work, because Windows XP did not come with .NET 2.0 installed (it wasn't even included in any of the service packs), so I installed it and tried once more. As I had suspected it might, everything worked.

In conclusion

If you find yourself still working with old versions of the .NET framework or the .NET runtime, you can still use and benefit from most features of C#6. I hope my small effort here is helpful. If you have anything to add, please comment.

Here Lies The Example Code6

using System;

using System.Collections.Generic;

using static System.Math;

namespace System.Runtime.CompilerServices

{

[AttributeUsage( AttributeTargets.Method )]

public class ExtensionAttribute : Attribute

{

}

}

namespace CSharp6andNET2

{

internal class Program

{

public delegate bool Filter( ArgumentException ex, string argName );

public bool DoFilter( Filter test, ArgumentException ex, string argName )

{

return test( ex, argName );

}

private static void Main( string[] args )

{

Filter x = ( ArgumentException ex, string argName ) => ex.ParamName == argName;

for ( int count = 0; count < 2; count++ )

{

try

{

ExceptionFilterTest( count == 0 );

}

catch ( ArgumentException e ) when (x( e, "argumentName" ))

{

Console.WriteLine( "Logged filtered exception" );

var test = new TestClass();

Console.WriteLine(

$"{nameof( test.Count )}: {test.Count}, {nameof( test.Count2 )}: {test.Count2}{nameof( test.Count3 )}: {test.Count3}, {nameof( test.Count4 )}: {test.Count4( 1 )}" );

var list = new List<int>

{

"9",

"25",

"36",

16,

4,

64

};

Console.WriteLine( "List" );

foreach ( var n in list )

{

Console.WriteLine( Sqrt( n ) );

}

var dictionary = new Dictionary<int, string>

{

[ 4 ] = "Test",

[ 2 ] = null,

[ 45 ] = null,

[ 34 ] = null,

[ 200 ] = null,

[ 16 ] = "Another test"

};

foreach ( var k in dictionary )

{

Console.WriteLine( $"{k.Key}: {k.Value?.Substring( 0, 3 )}" );

}

}

catch ( Exception )

{

Console.WriteLine( "Logged exception" );

}

}

}

private static void ExceptionFilterTest( bool filterable )

{

if ( filterable ) throw new ArgumentException( "Exception", "argumentName" );

throw new Exception( "Exception" );

}

}

internal static class Extensions

{

public static void Add( this List<int> list, string value )

{

list.Add( Int32.Parse( value ) );

}

}

internal class TestClass

{

public int Count { get; } = 6;

public int Count2 { get; set; } = 6;

public int Count3 => 6;

public int Count4( int x ) => x + 6;

}

}

- Async/await requires the TPL classes in the BCL, extension methods need the ExtensionAttribute, and exception filters require some runtime support [↩]

- The Elvis's [↩]

- very brief [↩]

- I realise many of the C#6 features could be left untested for similar reasons since almost all are compiler changes that do not need framework support, but testing it rather than assuming it is kind of the point [↩]

- Waited an hour for the IE XP virtual machine to download and then get it running [↩]

- Demonstrable purposes only; if you take this into production, on your head be it [↩]