Last time in this series on Octokit we looked at how to get the commits that have been made between one release and another. Usually, these commits will contain noise such as lazy commit messages and merge flog ("Fixed it", "Corrected spelling", etc.), merge commits, or commits that formed part of a larger feature change submitted via pull request. Rather than include all this noise in our release note generation, I want to filter those commits and either remove them entirely, or replace them with their associated pull request (which hopefully will be a little less noisy).

Before we filter out the noise, it seems prudent to reduce the commits to be filtered by matching them to pull requests. As with commits, we can query pull requests using a specific set of criteria; however, though we can request the results be sorted a certain way, we cannot specify a date range. To get all the pull requests that were merged before our release, we need to query for all the pull requests and then filter by date locally.

This query can be slow, since we are getting all closed pull requests in the repository. We could speed it up by providing a base branch name in the query criteria. However, to remove as much commit noise as possible, I would like to include pull requests that were merged to a different branch besides just the release branch1. We could make things more performant by managing a list of active release branches and then querying pull requests for each of those branches only rather than the entire repository, but for now, we will stick with the less optimal approach as it keeps the code examples a little cleaner.

var prRequest = new PullRequestRequest

{

State = ItemState.Closed,

SortDirection = SortDirection.Descending,

SortProperty = PullRequestSort.Updated

};

var pullRequests = await gitHubClient.PullRequest.GetAllForRepository("RepositoryOwner", "RepositoryName", prRequest);

var pullRequestsPriorToRelease = pullRequests

.Where(pr => pr.MergedAt < mostRecentTwoReleases[0].CreatedAt);

Before we can start filtering our commits against the pull requests, we need to get the commits that comprise each pull request. When requesting a collection of items (like we did for pull requests), the GitHub API returns just enough information about each item so that we can filter and identify the ones we really care about. Before we can do things with other properties on the items, we have to request additional information. More information on each pull request can be obtained about a specific pull request by using the `Get`, `Commits`, `Files`, and `Merged` calls. The `Get` call returns the same type of objects as the `GetAllForRepository` method, except that all the data is now populated instead of just a few select properties; the `Merged` call returns a Boolean value indicating if the PR has been merged (equivalent to the `Merged` property populated by `Get`); the `Files` method returns the files changed by that pull request; and the `Commits` method returns the commits.

var commitsForPullRequest = await gitHubClient.PullRequest.Commits("RepositoryOwner", "RepositoryName", pullRequest.Number);

At this point, things are looking pretty good: we can get a list of commits in the release and a list of pull requests that might be in the release. Now, we want to filter that list of commits to remove items that are covered by a pull request. This is easy; we just compare the hashes and remove the matches.

var commitsNotInPullRequest = from commit in commitsInRelease

join prCommit in prCommits on commit.Sha equals prCommit.Sha into matchedCommits

from match in matchedCommits.DefaultIfEmpty()

where match == null

select commit;

Using the collection of commits for the latest release, we join the commits from the pull requests using the SHA hash and then select all release commits that have no matching commit in the pull requests2. However, we don't want to lose information just because we're losing noise, so we have to maintain a list of the pull requests that were matched so that we can build our release note history. To keep track, we will hold off on discarding any information by pairing up commits in the release with their prospective pull requests instead of just dropping them.

Going back to where we had a list of pull requests merged prior to our release, let us revisit getting the commits for those pull requests and this time, pairing them with the commits in the release to retain information.

var commitsFromPullRequests = from pr in pullRequestsPriorToRelease

from commit in github.PullRequest.Commits("RepositoryOwner", "RepositoryName", pr.Number).Result

select new {commit,pr};

var commitsWithPRs = from commit in commitsInRelease

join prCommit in commitsFromPullRequests on commit.Sha equals prCommit.commit.Sha into matchedPrCommits

from matchedPrCommit in matchedPrCommits.DefaultIfEmpty()

select new

{

PullRequest = match?.pr,

Commit = commit

};

Now we have a list of commits paired with their parent pull request, if there is one. Using this we can build a more meaningful set of changes for a release. If I run this on the latest release of the Octokit.NET repository and then group the commits by their paired pull request, I can see that the original list of 135 commits would be reduced to just 58 if each commit that belonged to a pull request were bundled into just one entry.

Next, we need to process the commits to remove those representing merges and other noise. These are things to discuss in the next post of this series where perhaps we will take stock and see whether this effort has been valuable in producing more meaningful release note generation. Until then, thanks for reading and don't forget to leave a comment.

- often changes are merged forward from one branch to another, especially if there are multiple release branches to support patch development and such [↩]

- The `join` in this example is an outer join; we are taking the join results and using `DefaultIfEmpty()` to supply an empty collection when there was nothing to join [↩]

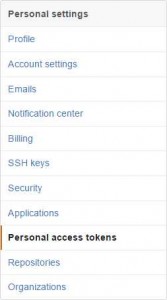

First, log into your GitHub account and choose Settings from the drop-down at the upper-right. On the fight, select Personal Access Tokens.

First, log into your GitHub account and choose Settings from the drop-down at the upper-right. On the fight, select Personal Access Tokens.

After a dismissing using git locally to perform this task (I figured those who might need this tool would probably not want to get the repository locally) and reading up on the

After a dismissing using git locally to perform this task (I figured those who might need this tool would probably not want to get the repository locally) and reading up on the