Photo by Ben White on Unsplash

For my final post of 2019, I thought I would deal with some serious FOMO1 by adding one of my own to the legions of year-end listicles adorned by clickbait headlines. You will not believe what's at number four! Nevermore shall I lament having passed up the opportunity to proffer a subjective collection of arbitrary length for your attention. Of what engrossing subject shall this list be? Life achievements? 11 places to visit before you die? Things I have discovered when looking for other things that I have lost? Nay, it shall be tools! Tools, I say. To be specific, development tools for it is tools of software development that I use often. To be even more specific, this is a list of development tools for each of which I could write an additional list of killer features, extensions, and magical whosywotsits. I present to you a list of feature packed fancies for fruitful software fabrication. How many tools? Read on to find out2.

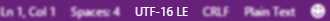

Visual Studio Code

code.visualstudio.com

This open source, cross platform, integrated development environment (IDE) backed by Microsoft really is the best I have used so far. With its built-in terminal, text editor, and task engine, it really is an integrated environment where, if it weren't for Slack and my web browser, I would spend all of my software crafting days. In fact, if I liked the extensions that integrated Slack and web browsing into Visual Studio Code, I could use it or them too; but I don't, so I don't.

Unlike IDE's of old, Visual Studio Code – often referred to as just VS Code or Code (it's command line invocation is the delightful code the-file-I-want-to-edit.js), is implemented to avoid having opinions about the code you write. Instead, it is written to support your code dictating how you write code so that you can deftly move between projects without worrying that the settings for one team will somehow traipse all over the settings for another.

If you like vim-style editors, there's a vim emulator. If you don't like the menus, use Zen Mode or go fullscreen. Want to run tests integrated in the sidebar or the test file itself? Do that. Want to run them from a terminal or via a background task? Do that instead. I could (and probably will) write a whole new list on the best extensions to use with Visual Studio Code. It is versatile enough that I believe any developer could make it the editor they need.

Why it is great for software developers?

Either natively or via an extension, Visual Studio Code supports just about every aspect of the software development lifecycle you might encounter, on every platform that likely matters (Windows, macOS, and Linux), using any workflow that suits you. Not to mention it gets feature updates monthly and is supported by a huge community of users. It takes a little DNA from editors like Atom, Sublime, and your basic text editor, and elevates them to something, well, sublimer3.

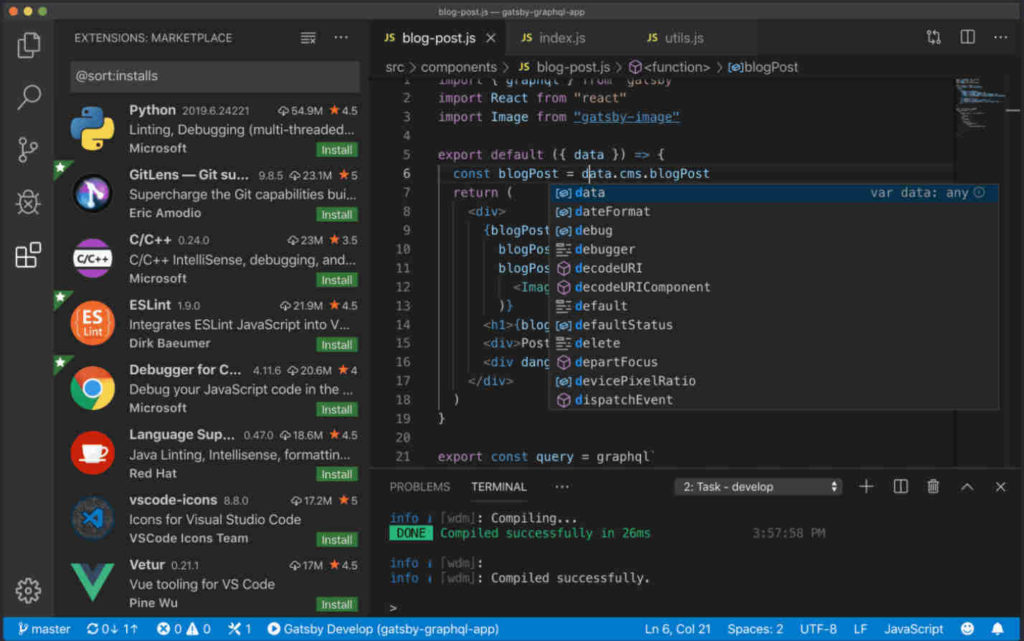

WordPress

wordpress.org

When concentrating on software development tools, it is really easy for me to overlook this one – probably because it is not a software development tool, at least not from first impressions. I use WordPress for this blog; I always have. There are many alternatives out there; some more technically involved than others. I know I could use markdown in a GitHub repository; I have heard of Jekyll and Gatsby and so many other ways to generate a site; I know about Medium, but for me, WordPress wins because it has the features I need, including wide support for hosting, accessibility, themes, plugins, and autonomy from the whimsy and money-grabbing aggregation platforms like Medium.

The recent updates to the core editing experience, known as Gutenberg, have been amazing and the regular updates that are auto-applied without me raising a finger keep adding polish to an already awesome experience. I can schedule posts, manage comments, and use plugins to add syntax highlighting, footnotes, multi-factor authentication, backups, and spam filtering, to name just a few. Just as with Visual Studio Code extensions, I could write another list of plugins that I love for WordPress.

35% of the web uses WordPress, from hobby blogs to the biggest news sites online.

https://wordpress.org/

WordPress is used by over a third of the web. A third! That includes this blog, almost every site that Ann Arbor Give Camp has worked on in the past few years, and rollingstone.com! If you are considering putting together any kind of website, whether a blog, or something else, I highly recommend this freely available platform that has more versatility than Meryl Streep.

Why it is great for software developers?

As I mentioned earlier, WordPress seems entirely unrelated to software development (unless you are writing themes and plugins for WordPress4). However, I have learned that writing a blog about ones technical exploits is an absolutely amazing software development tool. I never realised how much I could learn just by trying to teach someone else. I used to think a blog was about its readers and being right; I have come to learn that a blog is merely its writer, being. The act of writing a blog is where its value lies. Writing this blog identifies gaps in my knowledge, personal biases, and more. It can shine a light on my laziness, focus the my mind on a gnarly problem, and provide a scaffold from which to hang my personal growth. There are numerous times where writing posts for this blog (including some I never published) has helped me become a better software engineer. The fact that sometimes, someone reads it and finds it useful, entertaining, or infuriating is really just a bonus.

Write a blog. Hold an opinion. It is worth it.

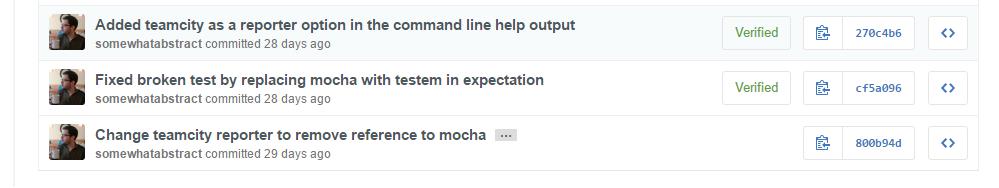

GitHub

github.com

For some readers, this may seem a pointless entry. Using GitHub for collaborative software development is so incredibly common that suggesting folks should use it seems a bit like suggesting folks should try breathing air5. Though there are alternatives such as GitLab, GitKracken6, or BitBucket, GitHub is almost ubiquitous. I do not recall an open source project that I have interacted with recently that was not hosted on GitHub7. With the recent changes allowing private and public repositories for personal accounts, the addition of GitHub Actions for automating all kinds of workflows – free to open source, and some great improvements to code review that have been released or are in beta, GitHub is an absolutely fantastic tool for those developing software. Add to that the integrations with other tools that I use like Visual Studio Code, Slack, and third-party issue trackers such as Jira, and GitHub shines. Many feared that its acquisition by Microsoft would doom it to failure, yet the Microsoft of today is a wonderful curator of open source goodies, and it seems that we all get to reap the benefits.

Why it is great for software developers?

Free backup of your source code, code reviews, automated workflows, and more, all on a tried and tested platform with a huge community. Not only that, but if you want, you get to collaborate, build, and present work with that community8.

🤷🏻♂️ That's it…

I don't know about you, but lists are exhausting. I've only written about three things and I'm already done with everything and ready for a lie down. I do stand by this list though. I really thought about what to put on it, considering the various tools I have used, not only because I have to, but because I want to. I would choose these tools from the very start of a new project unlike some others I use that, while I like them, are specific to a technology (such as React Developer Tools), are only what I use because the circumstances call for it, or are not really that standout against alternatives that I could be using.

Of course, this is all my personal opinion drawn from my personal experience; you have absolutely no obligation to agree with me. In fact, you have every right to use anything but the things I mentioned above, remaining in your state of willful ignorance, knowing you are wrong, unwilling to accept the truth as a way of life 😈. Just kidding, these are development tools, not religions – what works for you, works for you. These work for me. Perhaps you agree and want to pat me on the back from my excellent choices, maybe you care to tell me your preferred alternatives or shout at me about mine, or perhaps you read the footnotes and really have something to say about privilege, toxicity, and portfolios – feel free to engage in the comments; let's talk 🤗.

And with that, I bid you well until the 🎆New Year and all the productive software shenanigans that await us in 2020. 🙇🏻♂️

- Fear Of Missing Out – a most annoying acronym, I find; why? no idea [↩]

- it's three, three tools [↩]

- don't you roll your eyes at me [↩]

- PHP? Ew! [↩]

- you really should, it is to die for [↩]

- mention-worthy, if only for the pun [↩]

- before GitHub, it was SourceForge, before the DevShare debacle – https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/SourceForge [↩]

- Side Note: I think it is perfectly fine not to have a portfolio; some of the best developers I know do not have any public source, or fancy stuff to show off. This weird obsession some folks have with portfolios feels like another toxic manifestation of privilege in the software development world, and I don't care for it. Let's share what we want (and are able) to share, and accept that if we don't, that doesn't mean we're shit developers. 💙 [↩]