Photo by Noom Peerapong on Unsplash

Some video sites, like YouTube, provide a way to change the playback speed of the video. This allows you to watch content faster or slower than the standard speed. It is an incredibly useful feature for many people and until earlier this year, I thought it was ubiquitous. I am so used to using it that when I wanted to watch a video and it was not available, I got quite frustrated1.

Thankfully, a colleague showed me that all is not lost and I want to share the magic with you.

Above is the video I wanted to watch (source). It is an interesting video packed with useful information about testing, but it is quite long. I really wanted to watch it, but I did not have a lot of time available, so decided to watch it at a faster speed. However, I could not find a way to adapt the playback speed within the site's user experience. What to do?

In swoops my colleague, via Slack, to remind me that I have browser developer tools at my finger tips, primed to let me make it happen anyway. You can make this happen on the Vimeo site, the TestDouble site, or even here, on my blog.

In the world of HTML5, videos are embedded in pages using the video element. The video element implements the HTMLMediaElement interface (as does the audio element) and if you can get a reference to the video element in JavaScript, you can use this interface to manipulate the video playback.

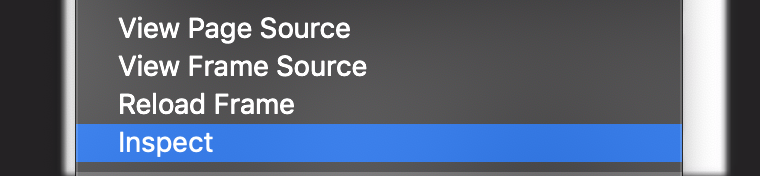

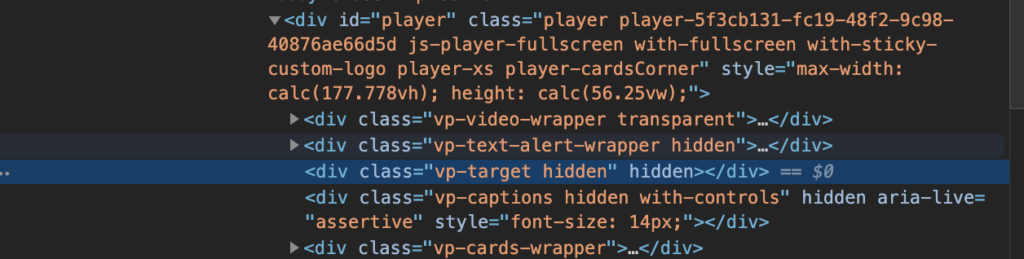

The first step is getting the element. I did this in Google Chrome, but you should be able to do this in other browsers too, though the commands may be different. I right-clicked on the video and selected Inspect.

This should open the developer tools, with a node highlighted.

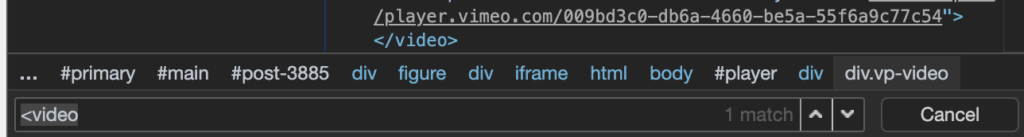

As seen in the screenshot above, the highlighted node was not the video element. Initially, I looked at the sibling elements and expanded likely candidates until I found the video tag I wanted, but there is an easier way. Use the Find command within the Elements tab of the Chrome developer tools by pressing ⌘+F (probably Ctrl+F on Windows).

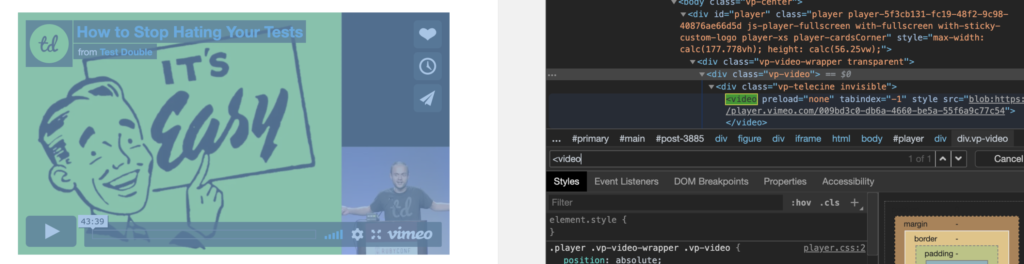

Within the find bar, you can type <video and it will find the first video element in the page and, if there are more, allow you to cycle through any others until you get to the one you want. You can even tell if it is the one you want or not as both the node and the corresponding video are highlighted as seen in the screenshot below.

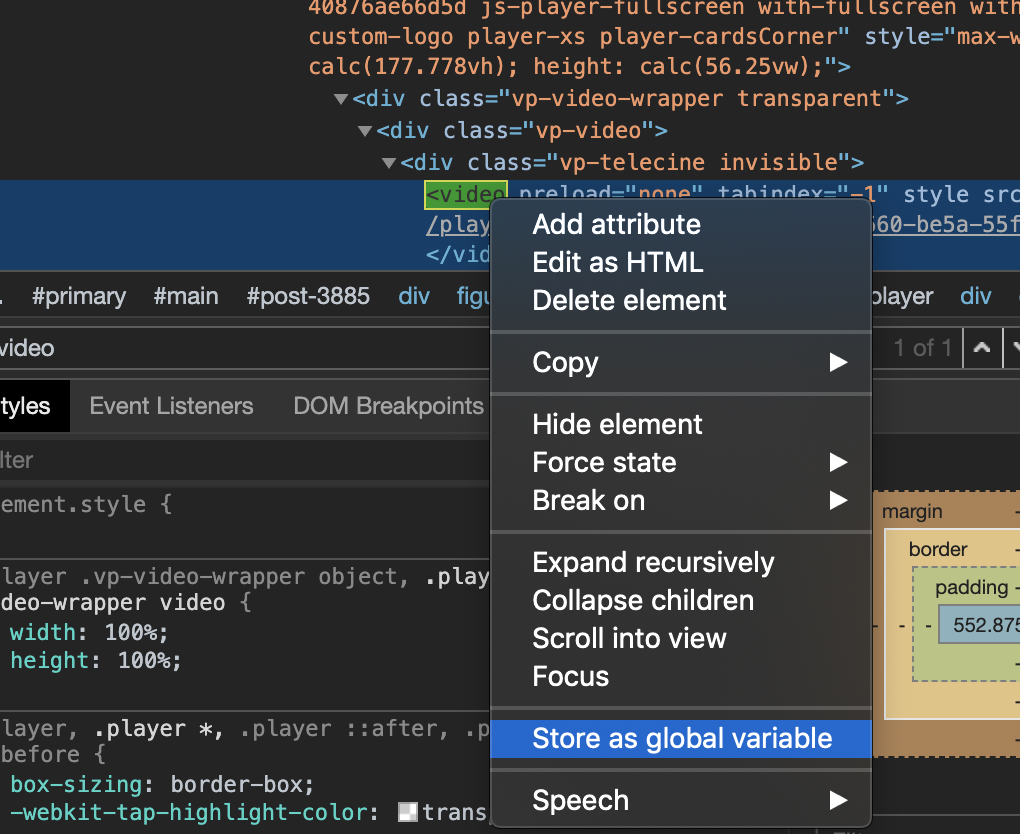

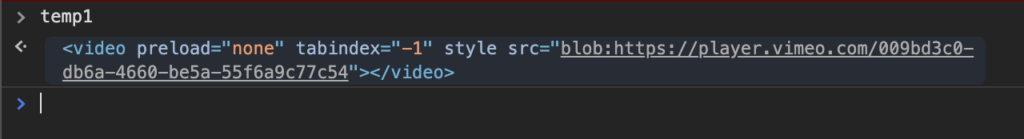

With the video element found, we can right click the DOM node in the developer tools and select Store as global variable.

This creates a global variable that we can use to manipulate the element. The console section is opened to show us the created variable and the element to which it refers.

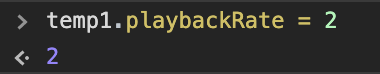

Now we can use the variable (temp1 in this case) to adjust the playback rate (or anything else we wanted to do). For example, if we want to run at double speed, just change playbackRate to 2 by entering temp1.playbackRate = 2.

And that's it. Hit play on that video and it will now be running at twice normal speed. Want it to run at half speed instead? Set playbackRate to 0.5 instead. Want it to run at normal speed again? Just set playbackRate to 1.

I hope y'all find this as helpful as I have and next time you stumble because a common feature appears to be lacking, don't be afraid to crack open those developer tools and see what magical hackery you can perform.

- "quite" is British for "inconsolably" [↩]