Since the start of the year, we have been taking a look at the various new features coming to C# in C#7. This week, we will look at some of the changes to returning values from our functions that are there for those who need better performance. Before we begin, here is a summary of what we are covering in this series.

- Binary literals

- Numeric literal digit separators

outvariablesthrowexpressions- Expression-bodied constructors

- Expression-bodied finalizers

- Expression-bodied property accessors

- Pattern matching

- Local functions

- Generalized async return types

reflocals and returns- Tuples

Generalized async return types

Up until now, an async method had to return Task, Task, or void (though that last one is generally frowned upon1). However, returning Task or Task can create performance bottlenecks as the reference type needs allocating. For C#7, we can now return other types from async methods, including the new ValueTask, enabling us to have better control over these performance concerns. For more information, I recommend checking out the official documentation.

Ref Locals and Ref Returns

C#7 brings a variety of changes to how we get output from our methods; specifically, out variables, tuples, and ref locals and ref returns. I covered out variables in an earlier post and I will be covering tuples in the next one, so let's take a look at ref locals and ref returns. Like the changes to async return types, this feature is all about performance.

The addition of ref locals and ref returns enable algorithms that are more efficient by avoiding copying values, or performing dereferencing operations multiple times.2

Like many performance-related issues, it is difficult to come up with a simple real world example that is not entirely contrived. So, suspend your engineering minds for a moment and assume that this is a perfectly great solution for the problem at hand so that I can explain this feature to you. Imagine it is Halloween and we are counting how many pieces of candy we have collectively from all of our heaving bags of deliciousness3. We have several bags of candy with different candy types and we want to count them. So, for each bag, we group by candy type, then retrieve current count of each candy type, add the count of that type from the bag, and then store the new count.

void CountCandyInBag(IEnumerable<string> bagOfCandy)

{

var candyByType = from item in bagOfCandy

group item by item;

foreach (var candyType in candyByType)

{

var count = _candyCounter.GetCount(candyType.Key);

_candyCounter.SetCount(candyType.Key, count + candyType.Count());

}

}

class CandyCounter

{

private readonly Dictionary<string, int> _candyCounts = new Dictionary<string, int>();

public int GetCount(string candyName)

{

if (_candyCounts.TryGetValue(candyName, out int count))

{

return count;

}

else

{

return 0;

}

}

public void SetCount(string candyName, int newCount)

{

_candyCounts[candyName] = newCount;

}

}

This works, but it has overhead; we have to look up the candy count value in our dictionary multiple times when retrieving and setting the count. However, by using ref returns, we can create an alternative to our dictionary that minimises that overhead. In writing this example, I learned4 that since IDictionary does not do ref returns from its methods, we can't use it with ref locals directly. However, we also cannot use a local variable as we cannot return a reference to a value that does not live beyond the method call, so we must modify how we store our counts.

void CountCandyInBag(IEnumerable<string> bagOfCandy)

{

var candyByType = from item in bagOfCandy

group item by item;

foreach (var candyType in candyByType)

{

ref int count = ref _candyCounter.GetCount(candyType.Key);

count += candyType.Count();

}

}

class CandyCounter

{

private readonly Dictionary<string, int> _candyCountsLookup = new Dictionary<string, int>();

private int[] _counts = new int[0];

public ref int GetCount(string candyName)

{

if (_candyCountsLookup.TryGetValue(candyName, out int index))

{

return ref _counts[index];

}

else

{

int nextIndex = _counts.Length;

Array.Resize(ref _counts, nextIndex + 1);

_candyCountsLookup[candyName] = _counts.Length - 1;

return ref _counts[nextIndex];

}

}

}

Now we are returning a reference to the actual stored value and changing it directly without repeated look-ups on our data type, making our algorithm perform better5. Be sure to check out the official documentation for alternative examples of usage.

Syntax Gotchas

Before we wrap this up, I want to take a moment to point out a few things about syntax. This feature uses the ref keyword a lot. You have to specify that the return type of a method is ref, that the return itself is a return ref, that the local variable storing the returned value is a ref, and that the method call is also ref. If you skip one of these uses of ref, the compiler will let you know, but as I discovered when writing the examples, the message is not particularly clear regarding how to fix it. Not only that, but you may get caught out when trying to consume by-reference returns as you can skip the two uses at the call-site (e.g. int count =); in such a case, the method call will be as if it were a regular, non-reference return; watch out.

_candyCounter.GetCount(candyName);

In Conclusion

I doubt any of us will use these performance-related features much, if at all, and nor should we. In fact, I expect that their appearance will be a code smell in a majority of circumstances; a case of "ooo, shiny" usage6. I certainly think that the use of ref return with anything but value types will be highly unusual. That said, in those situations when every nanosecond of performance is required, these new C# additions will most definitely be invaluable.

- https://msdn.microsoft.com/en-us/magazine/jj991977.aspx [↩]

- https://docs.microsoft.com/en-us/dotnet/articles/csharp/csharp-7#ref-locals-and-returns [↩]

- Let's not focus on why we went trick or treating as adults and why anyone gave us candy in the first place [↩]

- seems obvious now [↩]

- In theory; after all, this is a convoluted example and I am sure there are better ways to improve performance than just using ref locals. Always measure your code to be sure you are making things better; don't guess [↩]

- "Ooo, shiny" usage; when someone uses something just because it's new and they want to try it out [↩]

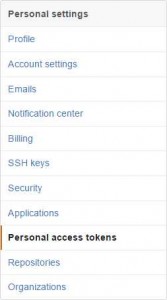

First, log into your GitHub account and choose Settings from the drop-down at the upper-right. On the fight, select Personal Access Tokens.

First, log into your GitHub account and choose Settings from the drop-down at the upper-right. On the fight, select Personal Access Tokens.